A History of WESU

Researched and written by James Cury and Freddi-Jo Eisenberg, Emily Weintraub, Evan Simko-Bednarski, and Leith Johnson.

(See even more! View our 80th Anniversary Exhibition here)

When sophomore Arch Doty moved into room 23 of Clark Hall in September, 1939, he brought with him a radio transmitter he had built at home the previous summer. Using a turntable, 78 rpm records, a microphone, the transmitter, and an antenna wire hanging out of Arch’s window, student-run radio at Wesleyan hit the airwaves.

It was a modest start. The entire audience that tuned into the evening AM-band broadcasts was limited to Clark residents—the weak signal reached no farther than several hundred feet beyond the antenna. But the broadcasts proved to be very popular, and within weeks, students in other residences wanted to be able to tune in.

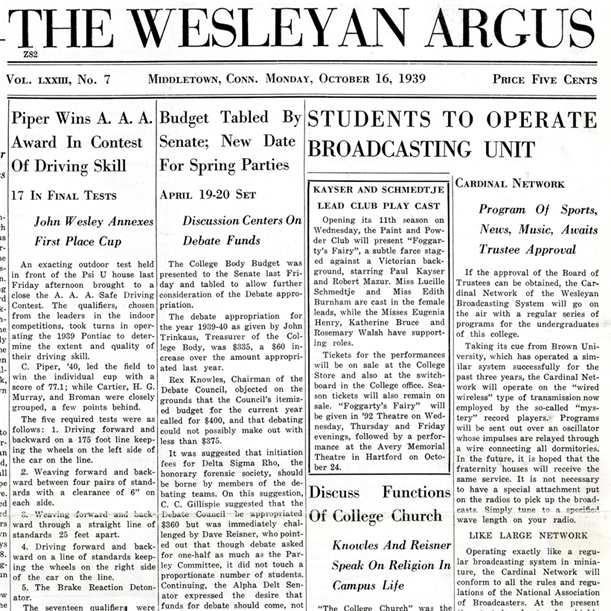

The only way to increase listenership was to extend the wire antenna. The Argus reported on October 16, 1939, that three (apparently self-appointed) student managers—Arch as technical director, Robert Stuart ’42 as operations manager, and George Strobridge ’41 as business manager—were seeking administration sanction to create a radio network at Wesleyan inspired by the one-of-a-kind station established by Brown University students in 1936 that used a wired network as a campus-wide antenna.

To get ready for the station’s upcoming formal debut, the students built a small studio and made technical improvements in a Clark basement space given to them by the administration. They ran hundreds of feet of wire among the existing cabling in the underground steam tunnels that connected Clark through Olin Library to two other buildings—Harriman Hall (now Public Affairs Center) and North College—that were dorms at the time. The wires were then connected to radiator pipes and as long as a radio was close enough, it would pick up the signal just like that of any other AM station. The student managers funded the entire enterprise out of their own pockets to the tune of $250 (about $4,200 in 2019).

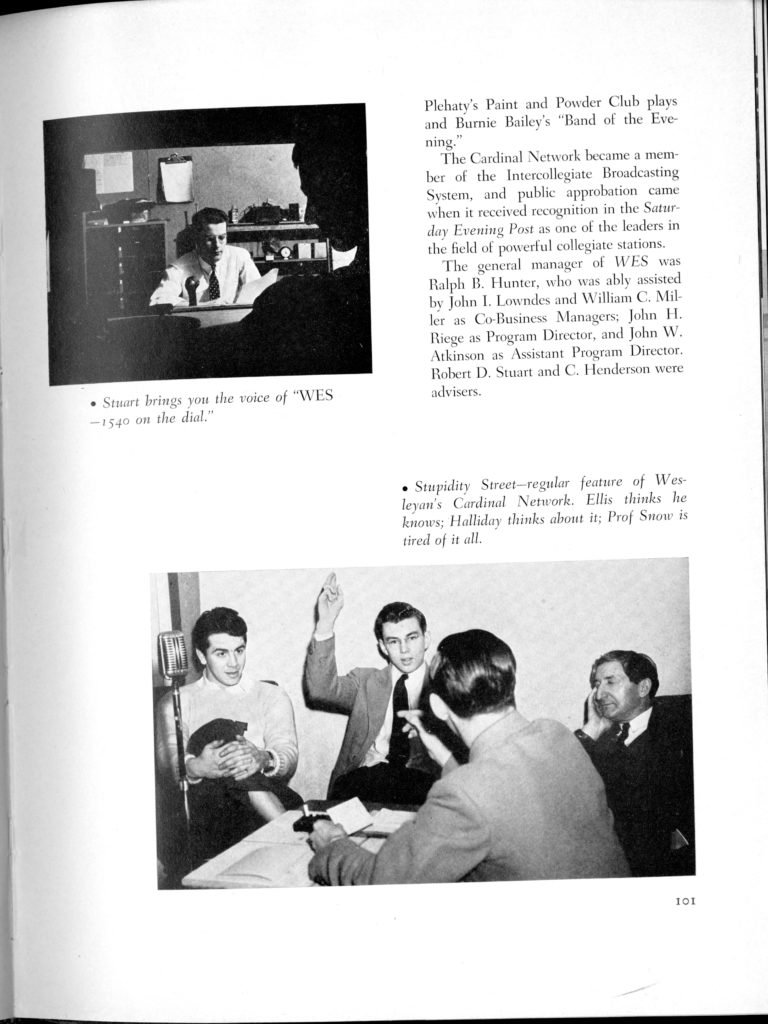

On November 9, 1939, at 8 p.m., radio station WES, as it was called prior to 1949, made its first official broadcast. It hasn’t been recorded what the first words were, but The Argus reported that the program opened with football captain Bob Murray ’40 speaking with cheerleader Dick Landsman ’41 about the upcoming Williams game. Then, football coach Jack Blott provided remarks about the game. President McConaughy followed with a 20-minute welcoming address (“Mr. Station Manager, Mr. Announcer, thank you for this privilege—cordial congratulations and good wishes”). Rounding out the broadcast, the Paint and Powder Club presented two scenes from their current production, Bury the Dead.

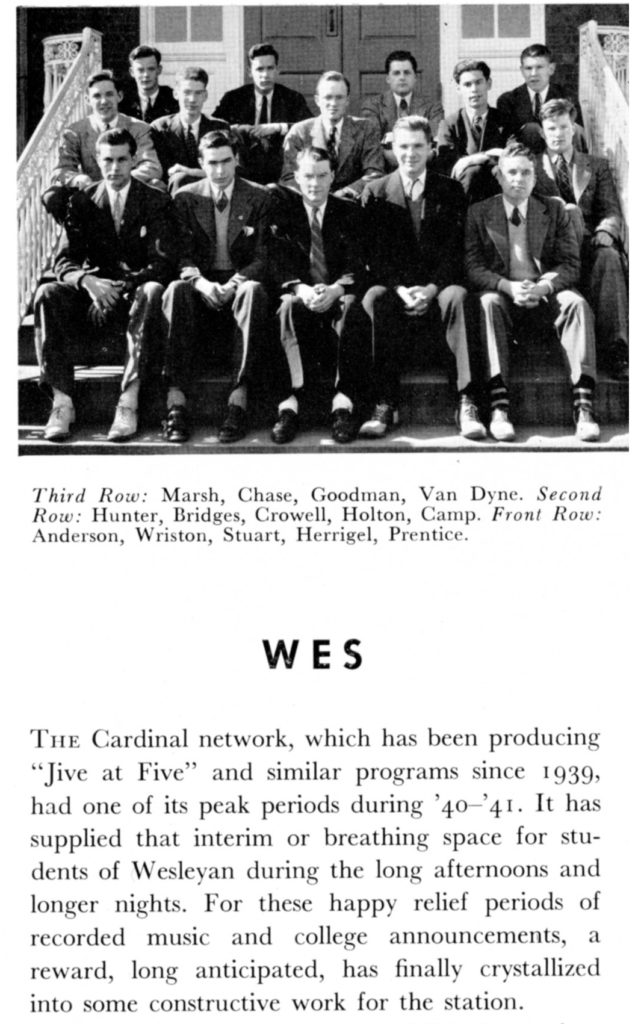

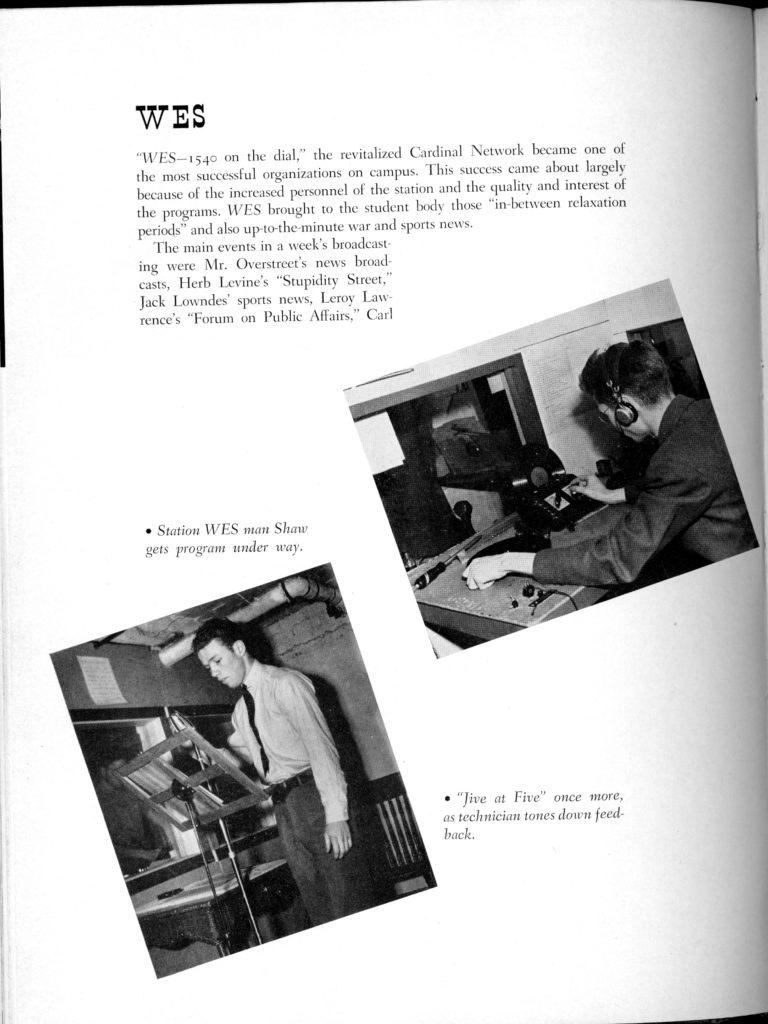

As WES gained in popularity, station managers were in negotiations with the fraternity houses in which many students lived across High Street that wanted the station’s signal for their parties. But the frat houses were not on the University’s utility grid, and the city of Middletown would not permit wires to be strung across High Street. In 1941, with the backing of the administration, the solution proved to be the inductance method—ask a physicist or electrical engineer what that is—that was used to connect the remainder of the campus buildings to what was called the Cardinal Network.

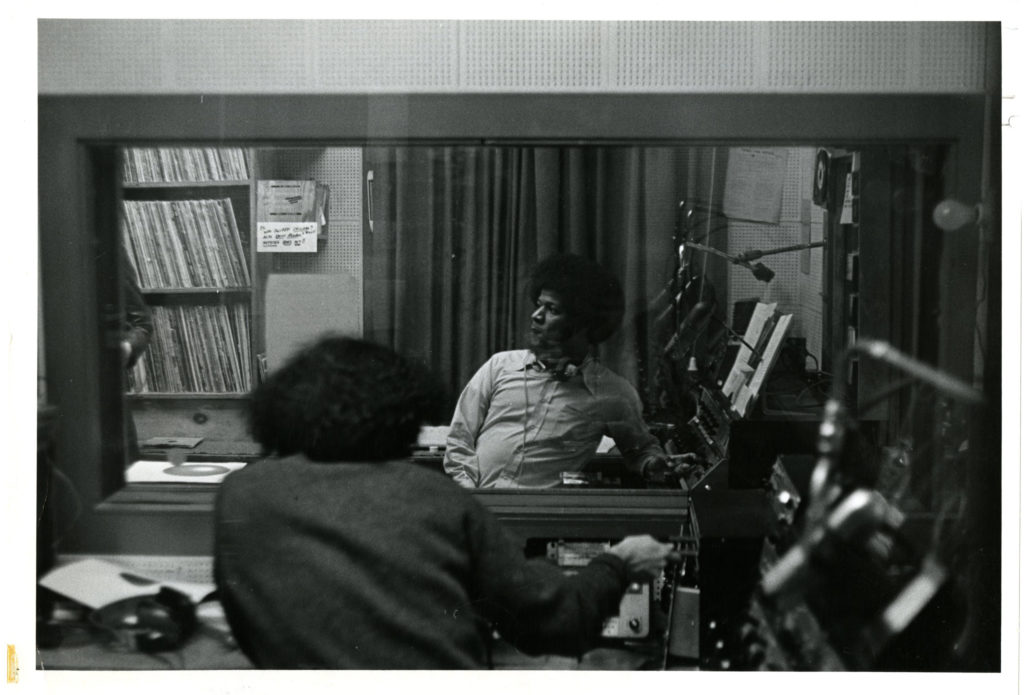

The early radio pioneers began construction of a legitimate studio in the basement of Clark Hall. Paying mostly out of pocket, they purchased studio equipment piece by piece, slowly constructing an elaborate headquarters, and a more powerful aerial antenna replaced the underground network.

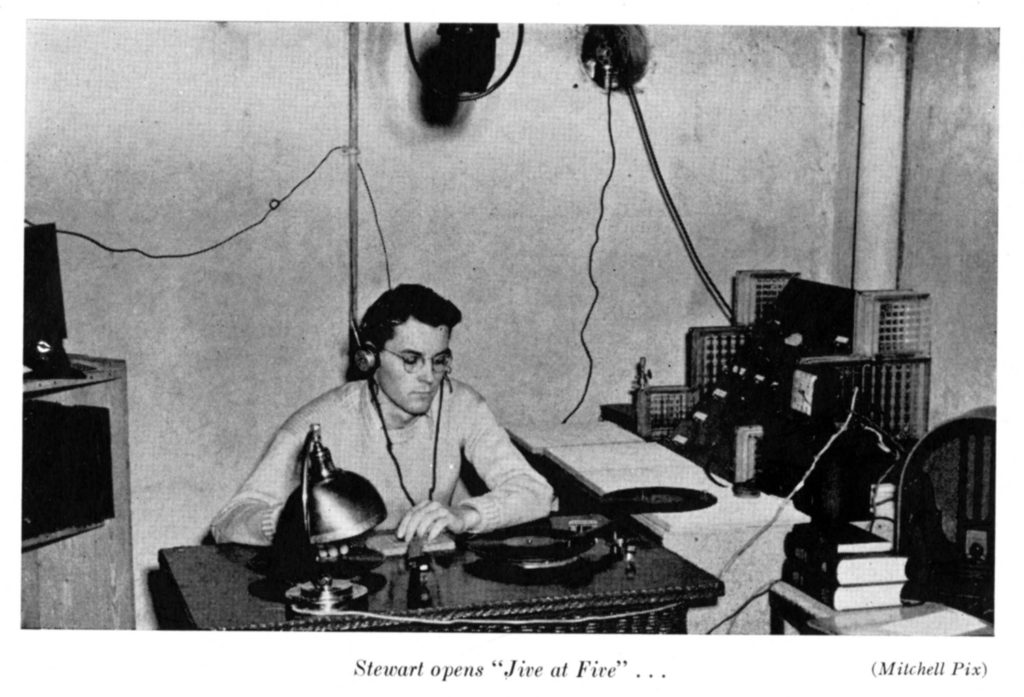

A swing show, “Jive at Five,” was WES’s first regular program, and it lives on today as a daily rundown of events of interest to the WESU audience. Other early shows included the “Grandfather’s Tales” horror stories program, weekly drama events, and play-by-play sports coverage.

Within two years of WES’s founding, Wesleyan was plunged into World War II. Navy men who were undergoing training on campus helped keep the station on the air. But, in 1946, shortly after the war, WES almost vanished. Howard Williams ’48, recounted this tale decades later:

“On the second day I was on campus, checking out Downey House bulletin board which contained room assignments, class schedules, notices of extra-curricular club meetings and other activities including the current films showing at the downtown movie house, plus a handwritten note that caught my eye. It said, ‘Anyone interested in Broadcast Radio meet me in the basement of Clark Hall at 3 o’clock this afternoon.’ The chap I found there turned out to be the last student left of a small group that had operated WES during the war. He was scheduled to be picked up in 15 minutes, was leaving Wesleyan having completed his studies and was headed for a distant part of the country. Since no one else had shown up he used the 15 minutes to tell me what he knew of the history of WES, conducted me on a tour of the control equipment, the turntables and volume controls, instructed me on how to put the station on the air, handed me a cardboard box full of papers including an F.C.C. document which he said was the equivalent of a Broadcast license and he was gone.”

After that, Williams pulled together a staff and the station stayed in business, with a range of programs, including live radio plays.

In 1949, the call letters WES were changed to WESU to conform with FCC regulations. Through the 1950s, the station became popular with the surrounding community, as it broadcast high school football games, and the news department covered such events as the Middletown mayoral elections.

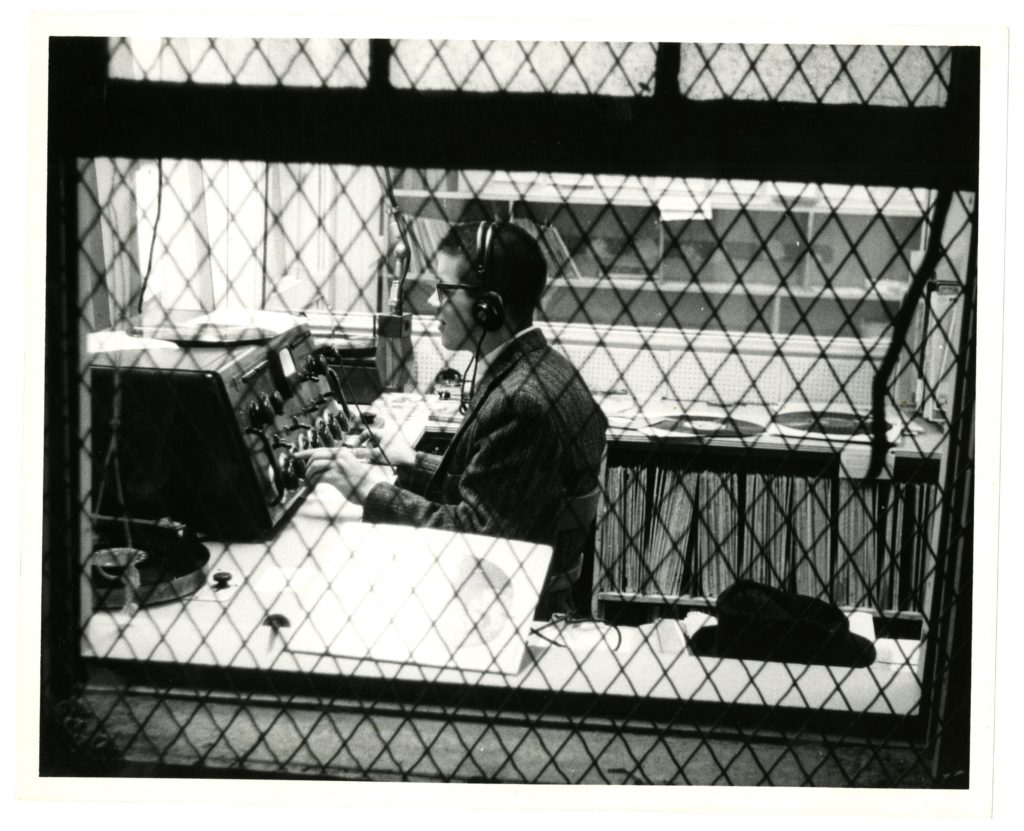

In 1961, the AM was disbanded and the FCC gave WESU a 10-watt FM educational station license at 88.1 on the radio dial. But in 1961, the new FM station was little more than a small operation with a meager record library and barely adequate used technical equipment. In 1965 and 1966, the station began recruiting incoming frosh, which led to the growth of staff from ten to about 75. In spite of the frustrations of poor equipment, a tight budget, and an almost non-existent audience, WESU stepped up its operation. The staff swelled in the next two years to over 200 and the hours of programming expanded to nearly 24 hours per day.

At the same time that WESU was experiencing a rapid resurgence, a major change in FCC policy brought about the next turning point in the station’s story. In 1967, the FCC announced that it planned to phase out all 10 watt stations. WESU was in jeopardy unless it could raise funds to cover an expansion. After recognizing the station’s educational role and its dedication to excellence, the board of trustees of Wesleyan University granted an allocation of $30,494, which would be about $200,000 in 2019, for an increase to 1,000 watts. In fact, the funding enabled the wattage to be increased to 1850, helped establish an AM station, and aided in the expansion of the studios and offices. Also in 1967, the Wesleyan trustees authorized the creation of the Wesleyan Broadcast Association, which was incorporated as a non-profit organization with the purpose of owning and managing the station. The WBA board consisted of students and one dean, but the dean had only advisory powers and no vote.

By 1968, the license, all equipment, and funds related to the station were transferred to the WBA, which was also exempt from paying rent for the Clark Hall facilities. The new license required that the station be non-profit, so for the first time in its history, the station could not allow advertising. Funding thus became dependent on the Wesleyan student government.

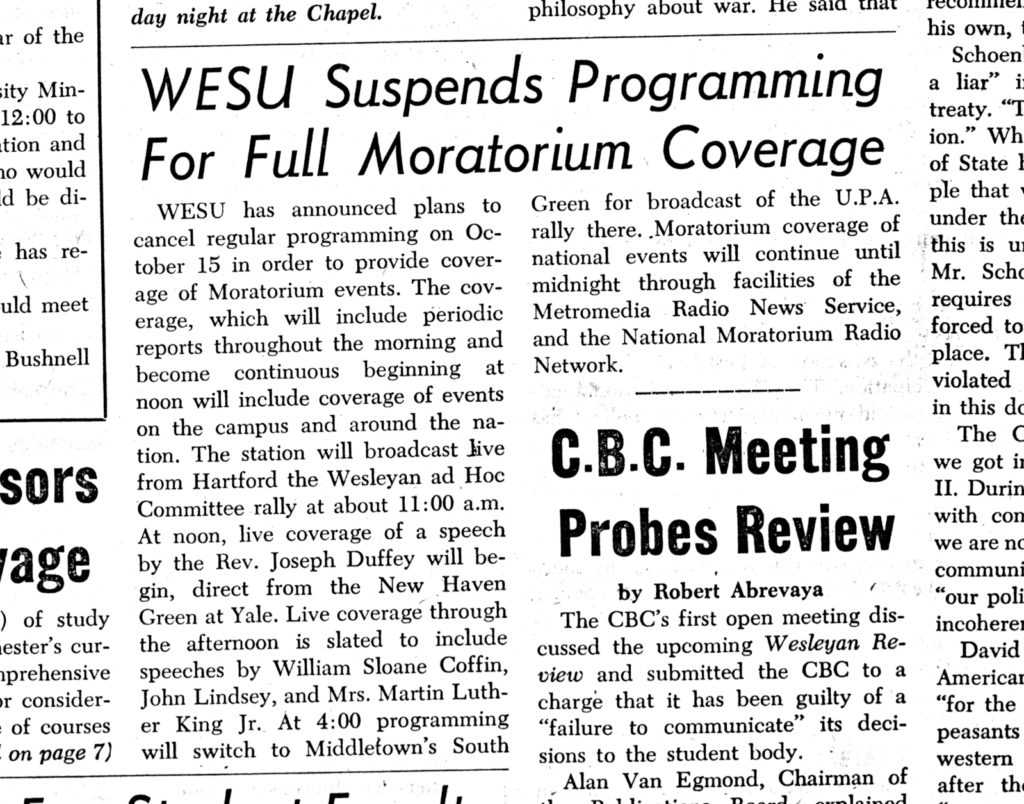

Here is just one example of WESU’s commitment to the campus community. During the Vietnam War, a nationwide day of protest called Moratorium was scheduled across the country on October 15, 1969. WESU suspended all of its normal broadcasting for the day and instead carried continuing coverage of the day’s happenings.

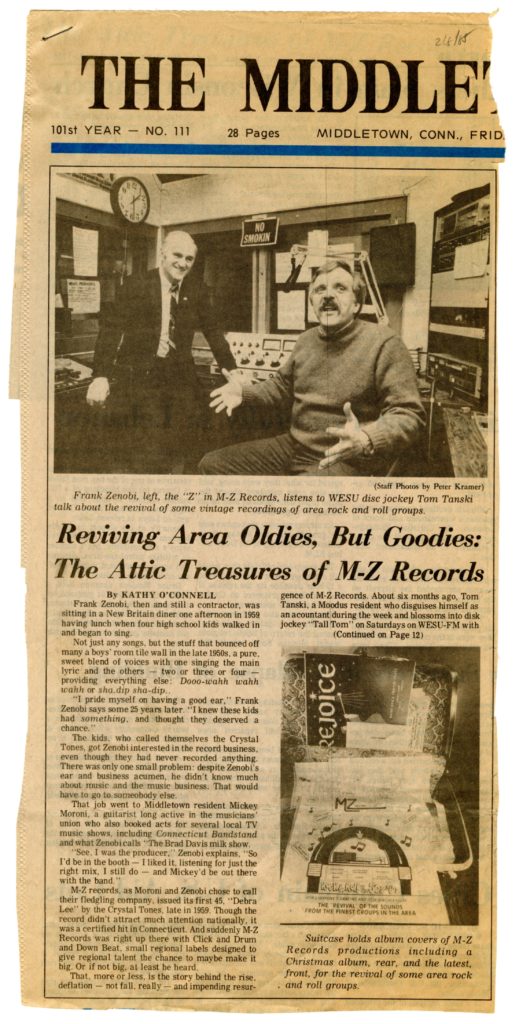

By the late 70’s, WESU had established itself as a home of eclectic music and the enemy of the Top 40. In at least one case, the station was willing to take a stand for its principles. In 1980, Arista Records responded to financial trouble in the record industry by revoking its free subscription service to all college radio stations. WESU was enraged, and then-Music Director Alex Crippen declared a boycott of Arista Records.

The announcement was published in a few college radio journals, and soon, many other stations around the country joined it. The boycott lasted for a year, until Arista started threatening legal action against larger, university-controlled stations, claiming that calls-to-action regarding the boycott, broadcast over the airwaves, were illegal. The validity of these claims was never tested, as the universities behind these larger stations urged the broadcasters to back out. The WESU-inspired resistance was short-lived, but it was a long time before WESU put any Arista records on the air.

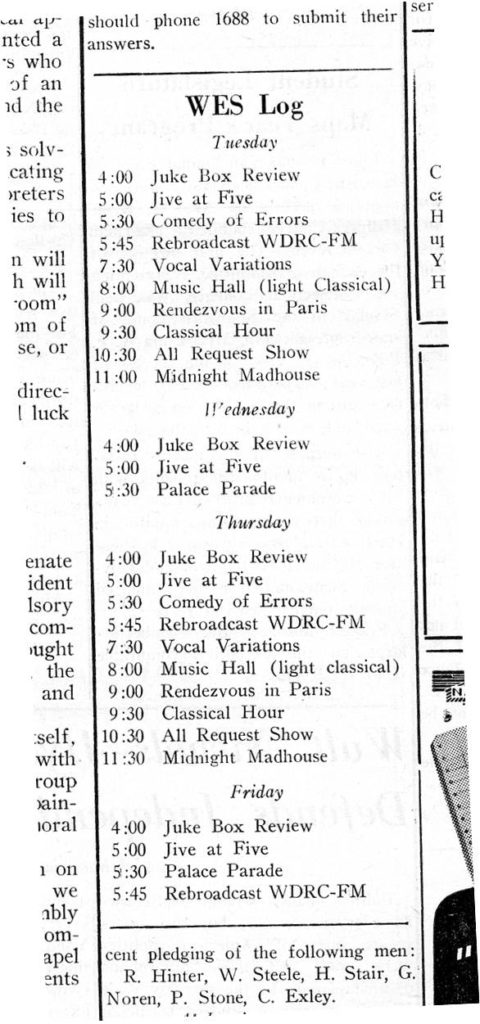

For the first fifty years of the station’s existence, the scheduling strategy for programs had been fundamentally the same: Generally, large consistent blocks of time were devoted to certain genres of music or certain types of cultural, news, or other kinds of programming. Below, you are looking at typical program schedule from the 1940s. We have programs featuring contemporary and classical music and variety, and they are generally scheduled at the same time each day, in a block scheduling format.

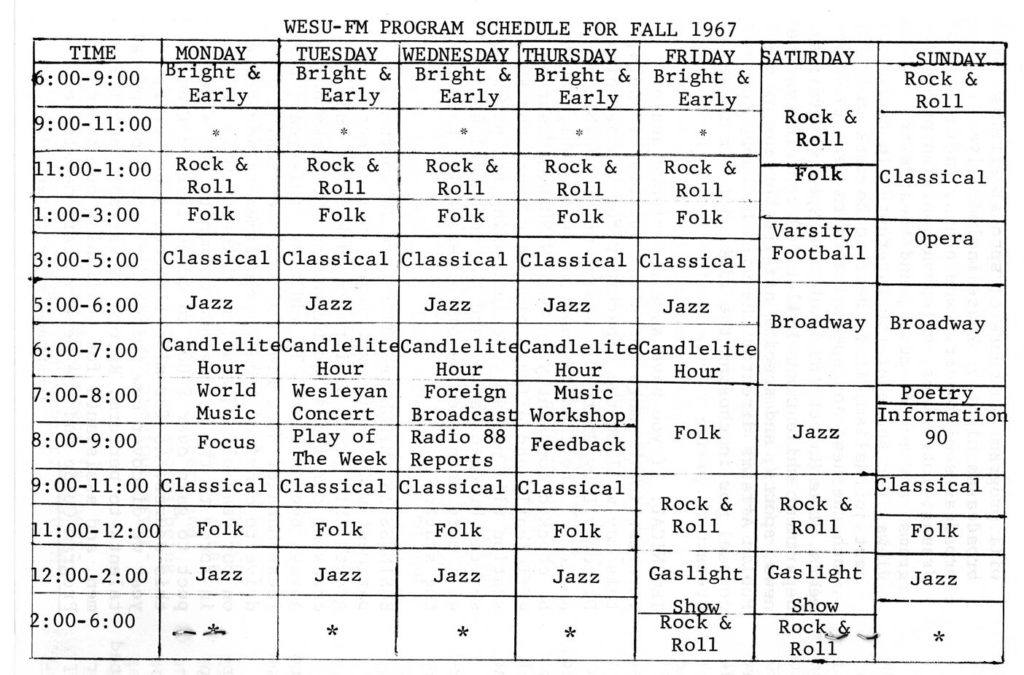

In the 1960s, the philosophy was still the same. Below is the FM schedule for 1967, and you can see the blocks of time reserved for certain kinds of music and programs. (At this time in the late 1960s, there was also a low-power Wesleyan AM station that was devoted primarily to rock music, but, even so, it, too, was block programmed.)

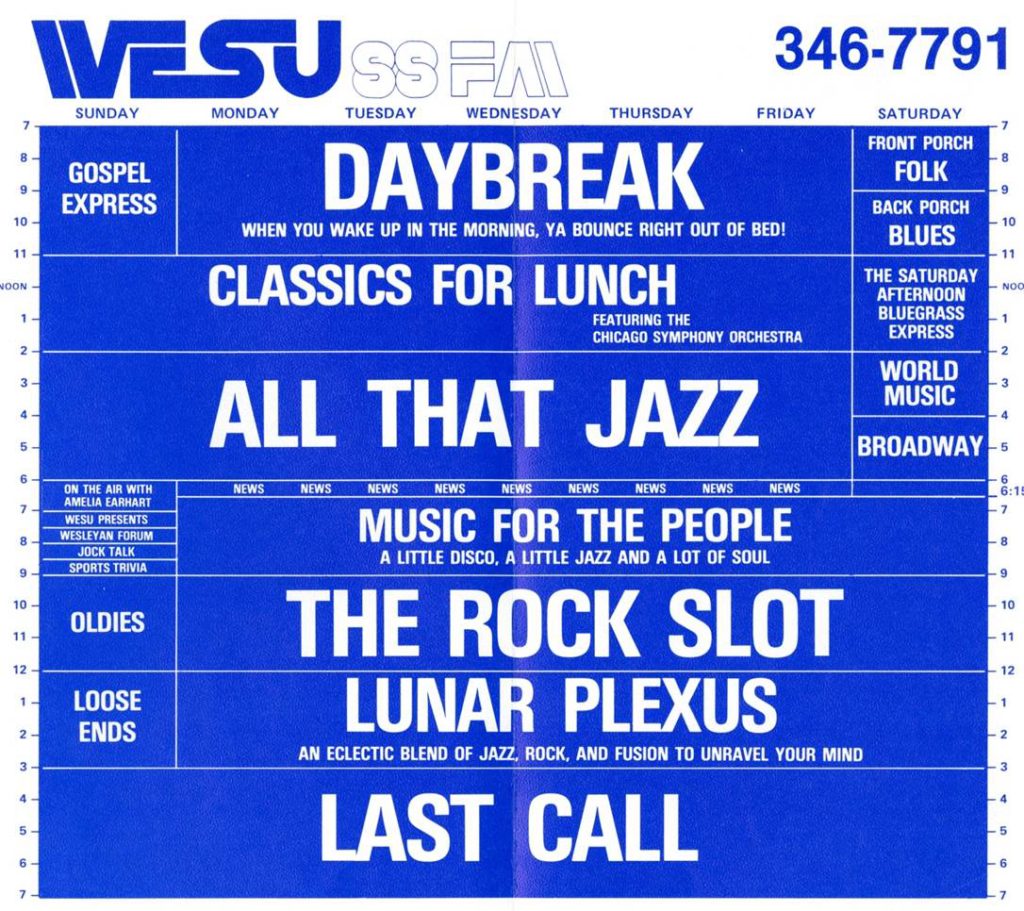

And once again, here is a typical program schedule from the 1980s. Block programming prevails and the listener can expect to hear certain kinds of music during certain times of the day and week.

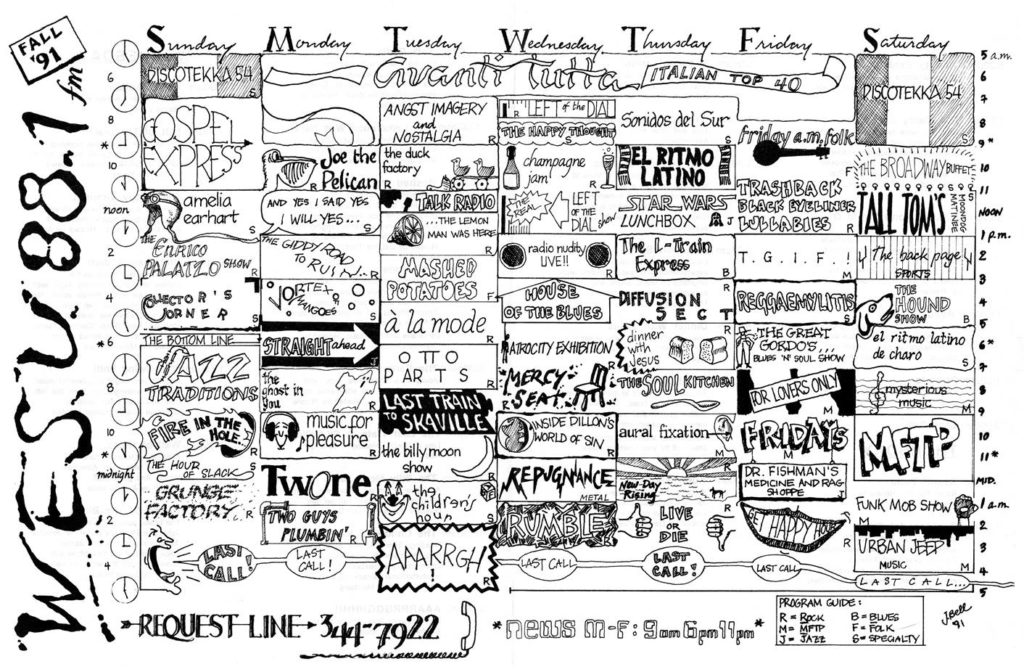

In 1989, that changed. WESU adopted freeform programming, which is the philosophy that is still embraced today. What is freeform programming? It’s illustrated in this program guide from fall 1991, and even if you can’t see the details, the lovely graphics give you an idea.

Here’s a definition of freeform provided by a WESU DJ in the early 90s:

Freeform is experimental because the programmer does not always know what the outcome of something will be. Freeform programming reflects the fact that how material is presented can be every bit as interesting as what the material is. Through freeform, a DJ can communicate complex ideas and concepts which could not be communicated through the use of language alone. For this reason, freeform radio is an art…good freeform radio is influenced by the community in which it operates. Programmers (‘composers’) must be aware of the context in which the sounds they broadcast will be received …our goal is to educate and entertain both ourselves and our listeners…I think that freeform, with its natural reliance on the juxtaposition of genres and styles, can be targeted to the average person. Radio is the soundtrack to many people’s lives, and freeform can make their lives more interesting.

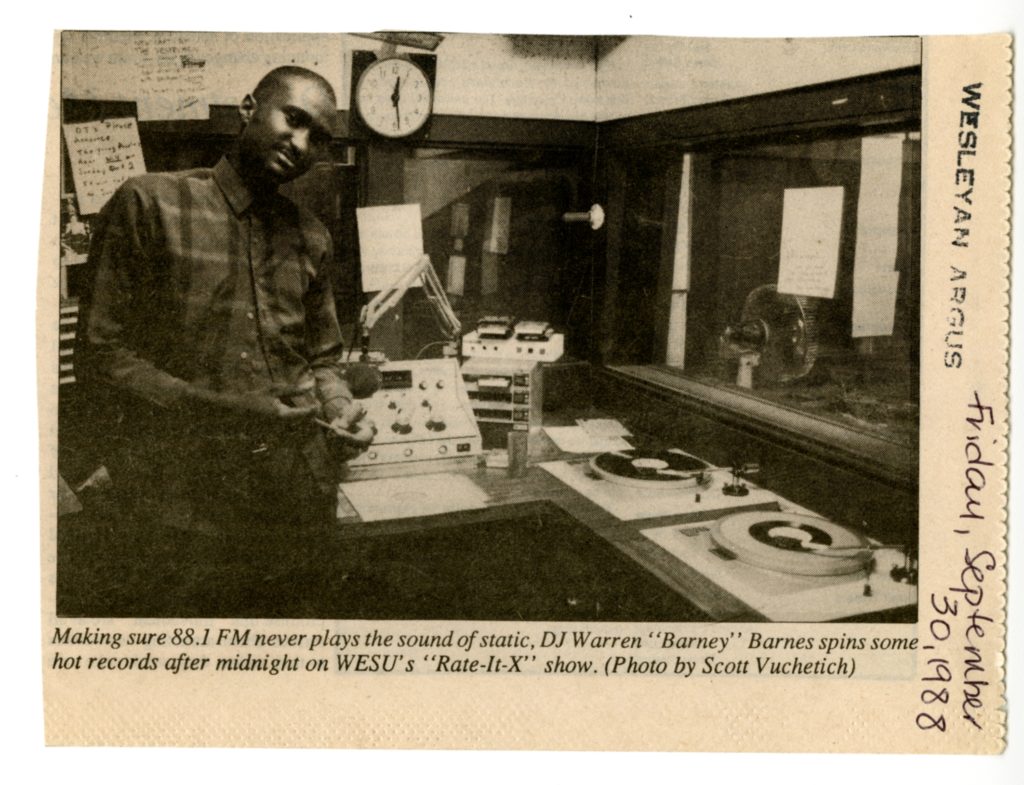

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, community members emerged as WESU’s most active link with the listening area. Community members served on the board and developed and broadcast thousands of hours of programming. The most enduring shows on today’s schedule have been produced by community DJs for decades and have large, loyal audiences. A major portion of the current programming is provided by community members.

The ’80s and ’90s were a time of great freedom on WESU. Eclectic music became more and more a part of the station’s identity. The local music program, The Living Edge, was syndicated nationally for several years. A course on broadcast journalism produced content for the station. More people than ever were free to be a part of WESU, and there were fewer restrictions on the kinds of shows they could produce. At the same time, however, the organizational side of the station was beginning to unravel. The position of the faculty advisor had long ago passed into obscurity, and though the station had managed quite well on its own, a series of events put the station in a tenuous financial position. In 1986, the transmitter unexpectedly began to falter and quickly became too unreliable for constant use. With equipment failure came strains on the budget, calls for assistance from the administration and student government, and debt. In 1990, for reasons that require more research, the WBA went under, the station was no longer independent, and it faced the task of rebuilding its financial base.

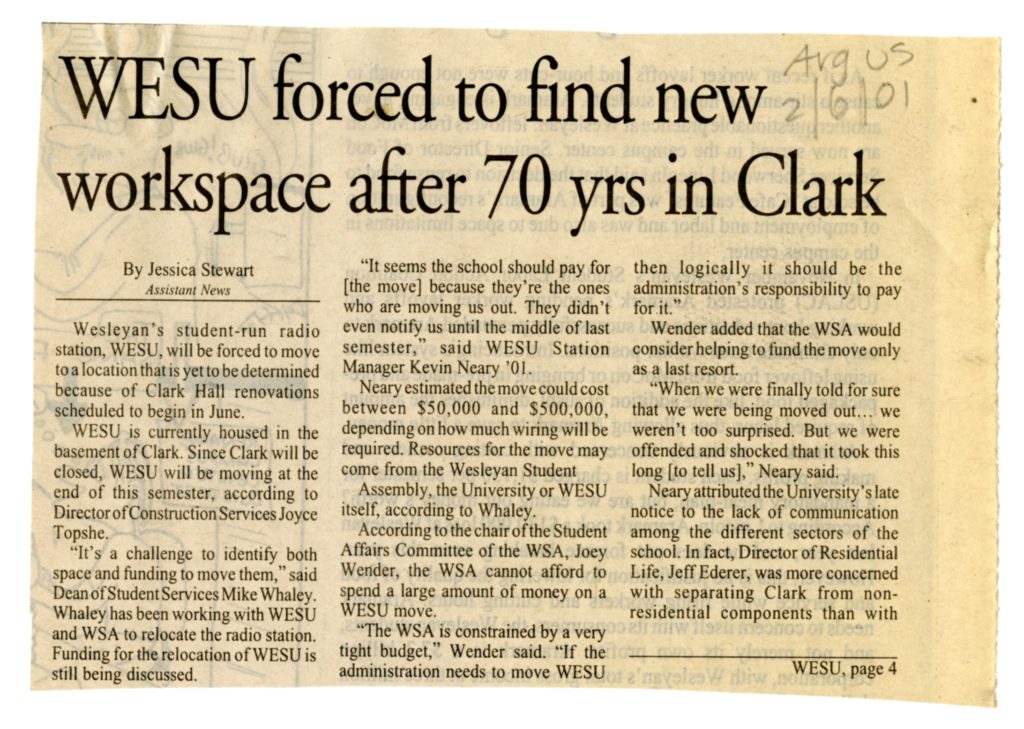

In 1999, Wesleyan University decided to commence its long-overdue renovation of Clark Hall. For about a decade, the administration had been in communication with WESU, trying to locate another comparable space for the station’s studios. Finally, in 2001, WESU moved into smaller quarters in its present location at 45 Broad Street. Unfortunately, in the course of the move, the station lost a good deal of music and archived documents.

In 2003, President Doug Bennet of Wesleyan University entered into negotiations with WESU’s board to acquire the license to 88.1. The reasoning was that the university was a far more stable institution financially, and could ensure greater safety for the license.

In 2004, the board decided that the best way to solidify its organizational structure was to attend to the four-year turnover. This would require the creation of a salaried general manager position, a person who could make a long-term commitment to stay with the station, and serve as a resource for the board, conveying experience and station history from year to year, as well as attending to the daily workings of the station. The university was approached to financially assist the station in creating this position. In 2005, the university, as license holder, decided that the best way to increase revenue was through simulcasting the shows of nearby NPR affiliate WSHU, thus receiving a cut of WSHU’s fundraising. The university, in return for facilitating the general manager position, necessitated that the board of directors become all-student.

In 2005, WESU held its first substantial on-air pledge drive and instituted a successful underwriting program making a very substantial step towards financial stability and independence. Through negotiations with the university, community volunteers were again able to serve on the board, which was been reorganized to better handle the new systems and needs that came about with the relationship with WSHU and the station’s attempts at financial and organizational stability and independence.

In 2006, WESU become an official affiliate to Pacifica Radio, the nation’s oldest public radio network. Through this affiliation, WESU had access to Pacifica’s renowned public radio archives and many other high quality public affairs programming.

In December 2006, WESU raised almost $20,000 in listener pledges during the 2nd Annual Winter Holiday Pledge Drive. For the second year in a row, according to the Hartford Advocate‘s Readers Poll, WESU is the third most listened to college radio station in the Hartford area. By the end of the 2006 fiscal year, WESU negotiated funding from the University for a new, part-time production assistant.

President Bennet retired in 2007. His involvement with WESU had been controversial, to say the least. Many resented the change he encouraged with the implementation of NPR programming in 2004 while others applauded the quality and consistency in programming that resulted from this new relationship.

Important initiatives were undertaken to ensure the continued development of the station. For our 2007 pledge drive, WESU raised over $20,000 in listener support, a first for the station. Programming was expanded to include more programs that connected WESU to the Wesleyan experience. Training was expanded and improved and began to accommodate more than forty students and community volunteers per semester. Programs such as Indigenous Politics and The Wesleyan Report connected WESU more than ever with the faculty and student community on campus, providing a valuable resource for the University and the central Connecticut region, as well as our online listeners. The Middletown Youth Radio Project ran daily workshops for Middletown youth itching to try their hands at every element that goes into producing a radio program. These initiatives and others marked the active and vibrant community of WESU.

Beginning in 2009, WESU began an earnest effort to upgrade the station’s signal four-fold from 1500 to 6000 watts. With assistance from the University, sister community stations, and the Middletown Community Health Center, WESU received the financial and technical assistance to complete the physical upgrade. The FCC granted WESU’s application to increase the station’s signal in the Fall of 2010.

See even more! View our 80th Anniversary Exhibition here.